The Second Half

tldr: We’re at AI’s halftime.

For decades, AI has largely been about developing new training methods and models. And it worked: from beating world champions at chess and Go, surpassing most humans on the SAT and bar exams, to earning IMO and IOI gold medals. Behind these milestones in the history book — DeepBlue, AlphaGo, GPT-4, and the o-series — are fundamental innovations in AI methods: search, deep RL, scaling, and reasoning. Things just get better over time.

So what’s suddenly different now?

In three words: RL finally works. More precisely: RL finally generalizes. After several major detours and a culmination of milestones, we’ve landed on a working recipe to solve a wide range of RL tasks using language and reasoning. Even a year ago, if you told most AI researchers that a single recipe could tackle software engineering, creative writing, IMO-level math, mouse-and-keyboard manipulation, and long-form question answering — they’d laugh at your hallucinations. Each of these tasks is incredibly difficult and many researchers spend their entire PhDs focused on just one narrow slice.

Yet it happened.

So what comes next? The second half of AI — starting now — will shift focus from solving problems to defining problems. In this new era, evaluation becomes more important than training. Instead of just asking, “Can we train a model to solve X?”, we’re asking, “What should we be training AI to do, and how do we measure real progress?” To thrive in this second half, we’ll need a timely shift in mindset and skill set, ones perhaps closer to a product manager.

The first half

To make sense of the first half, look at its winners. What do you consider to be the most impactful AI papers so far?

I tried the quiz in Stanford 224N, and the answers were not surprising: Transformer, AlexNet, GPT-3, etc. What’s common about these papers? They propose some fundamental breakthroughs to train better models. But also, they managed to publish their papers by showing some (significant) improvements on some benchmarks.

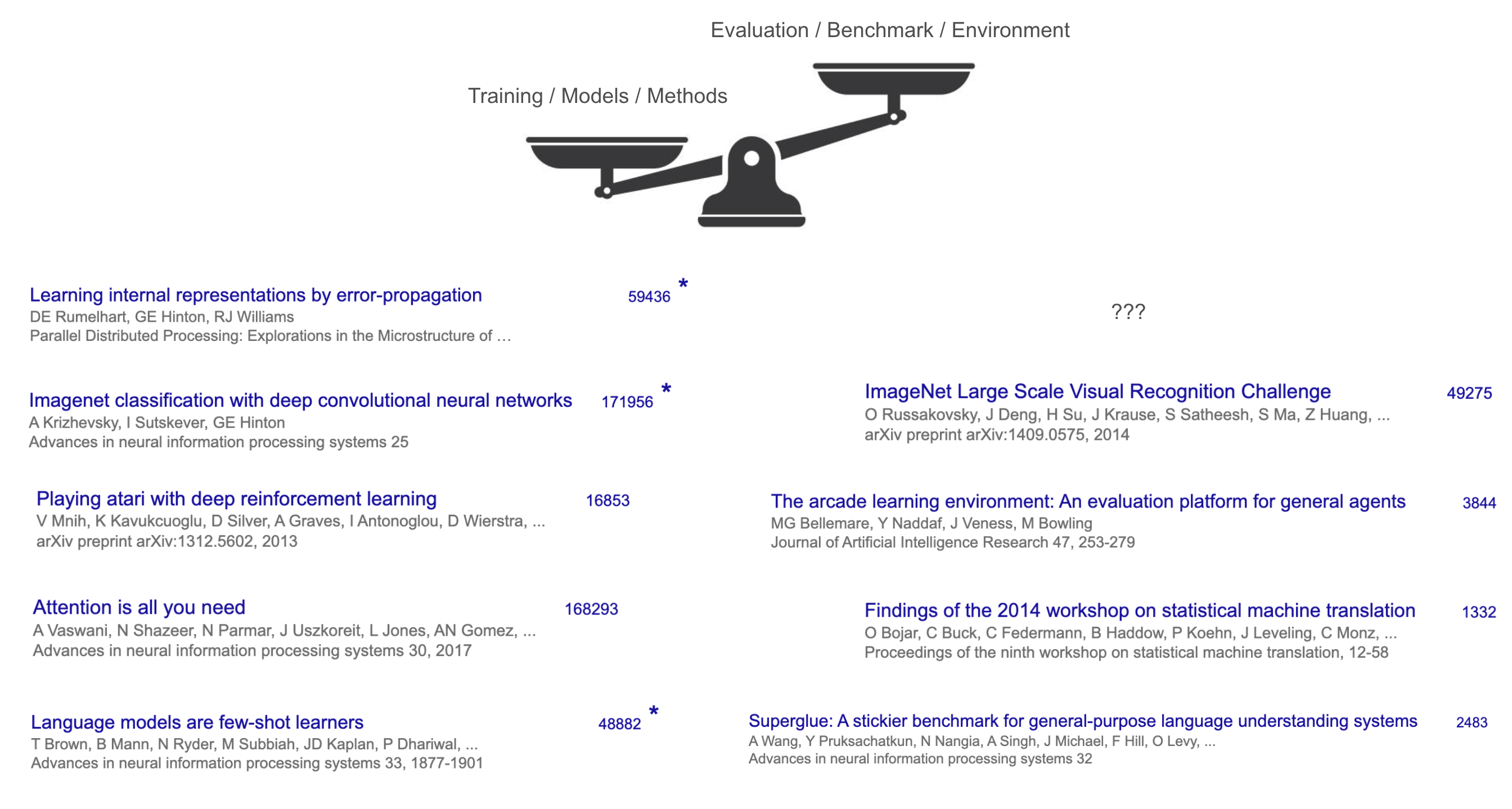

There is a latent commonality though: these “winners” are all training methods or models, not benchmarks or tasks. Even arguably the most impactful benchmark of all, ImageNet, has less than one third of the citation of AlexNet. The contrast of method vs benchmark is even more drastic anywhere else —- for example, the main benchmark of Transformer is WMT’14, whose workshop report has ~1,300 citations, while Transformer had >160,000.

That illustrates the game of the first half: focus on building new models and methods, and evaluation and benchmark are secondary (although necessary to make the paper system work).

Why? A big reason is that, in the first half of AI, methods were harder and more exciting than tasks. Creating a new algorithm or model architecture from scratch – think of breakthroughs like the backpropagation algorithm, convolutional networks (AlexNet), or the Transformer used in GPT-3 – required remarkable insight and engineering. In contrast, defining tasks for AI often felt more straightforward: we simply took tasks humans already do (like translation, image recognition, or chess) and turned them into benchmarks. Not much insight or even engineering.

Methods also tended to be more general and widely applicable than individual tasks, making them especially valuable. For example, the Transformer architecture ended up powering progress in CV, NLP, RL, and many other domains – far beyond the single dataset (WMT’14 translation) where it first proved itself. A great new method can hillclimb many different benchmarks because it’s simple and general, thus the impact tends to go beyond an individual task.

This game has worked for decades and sparked world-changing ideas and breakthroughs, which manifested themselves by ever-increasing benchmark performances in various domains. Why would the game change at all? Because the cumulation of these ideas and breakthroughs have made a qualitative difference in creating a working recipe in solving tasks.

The recipe

What’s the recipe? Its ingredients, not surprisingly, include massive language pre-training, scale (in data and compute), and the idea of reasoning and acting. These might sound like buzzwords that you hear daily in SF, but why call them a recipe??

We can understand this by looking through the lens of reinforcement learning (RL), which is often thought of as the “end game” of AI — after all, RL is theoretically guaranteed to win games, and empirically it’s hard to imagine any superhuman systems (e.g. AlphaGo) without RL.

In RL, there are three key components: algorithm, environment, and priors. For a long time, RL researchers focused mostly on the algorithm (e.g. REINFORCE, DQN, TD-learning, actor-critic, PPO, TRPO…) – the intellectual core of how an agent learns – while treating the environment and priors as fixed or minimal. For example, Sutton and Barto’s classical textbook is all about algorithms and almost nothing about environments or priors.

However, in the era of deep RL, it became clear that environments matter a lot empirically: an algorithm’s performance is often highly specific to the environment it was developed and tested in. If you ignore the environment, you risk building an “optimal” algorithm that only excels in toy settings. So why don’t we first figure out the environment we actually want to solve, then find the algorithm best suited for it?

That’s exactly OpenAI’s initial plan. It built gym, a standard RL environment for various games, then the World of Bits and Universe projects, trying to turn the Internet or computer into a game. A good plan, isn’t it? Once we turn all digital worlds into an environment, solve it with smart RL algorithms, we have digital AGI.

A good plan, but not entirely working. OpenAI made tremendous progress down the path, using RL to solve Dota, robotic hands, etc. But it never came close to solving computer use or web navigation, and the RL agents working in one domain do not transfer to another. Something is missing.

Only after GPT-2 or GPT-3, it turned out that the missing piece is priors. You need powerful language pre-training to distill general commonsense and language knowledge into models, which then can be fine-tuned to become web (WebGPT) or chat (ChatGPT) agents (and change the world). It turned out the most important part of RL might not even be the RL algorithm or environment, but the priors, which can be obtained in a way totally unrelated from RL.

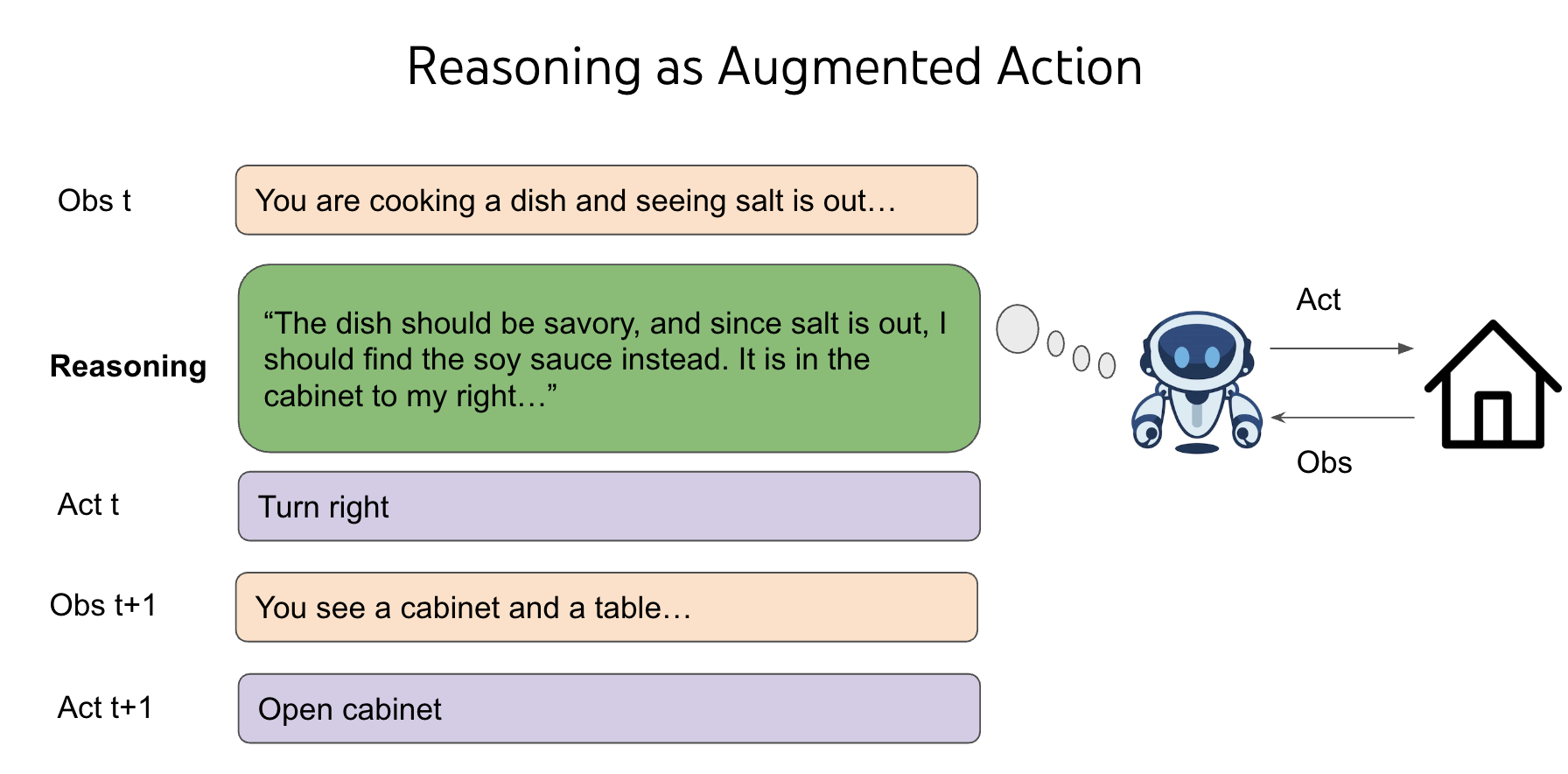

Language pre-training created good priors for chatting, but not equally good for controlling computers or playing video games. Why? These domains are further from the distribution of Internet text, and naively doing SFT / RL on these domains generalizes poorly. I noticed the problem in 2019, when GPT-2 just came out and I did SFT / RL on top of it to solve text-based games - CALM was the first agent in the world built via pre-trained language models. But it took millions of RL steps for the agent to hillclimb a single game, and it doesn’t transfer to new games. Though that’s exactly the characteristic of RL and nothing strange to RL researchers, I found it weird because we humans can easily play a new game and be significantly better zero-shot. Then I hit one of the first eureka moment in my life - we generalize because we can choose to do more than “go to cabinet 2” or “open chest 3 with key 1” or “kill dungeon with sword”, we can also choose to think about things like “The dungeon is dangerous and I need a weapon to fight with it. There is no visible weapon so maybe I need to find one in locked boxes or chests. Chest 3 is in Cabinet 2, let me first go there and unlock it”.

Thinking, or reasoning, is a strange kind of action - it does not directly affect the external world, yet the space of reasoning is open-ended and combintocially infinite — you can think about a word, a sentence, a whole passage, or 10000 random English words, but the world around you doesn’t immediate change. In the classical RL theory, it is a terrible deal and makes decision-making impossible. Imagine you need to choose one out of two boxes, and there’s only one box with $1M and the other one empty. You’re expected to earn $500k. Now imagine I add infinite empty boxes. You’re expected to earn nothing. But by adding reasoning into the action space of any RL environment, we make use of the language pre-training priors to generalize, and we afford to have flexible test-time compute for different decisions. It is a really magical thing and I apologize for not fully making sense of it here, I might need to write another blog post just for it. You’re welcome to read ReAct for the original story of reasoning for agents and read my vibes at the time. For now, my intuitive explanation is: even though you add infinite empty boxes, you have seen them throughout your life in all kinds of games, and choosing these boxes prepare you to better choose the box with money for any given game. My abstract explanation would be: language generalizes through reasoning in agents.

Once we have the right RL priors (language pre-training) and RL environment (adding language reasoning as actions), it turns out RL algorithm might be the most trivial part. Thus we have o-series, R1, deep research, computer-using agent, and so much more to come. What a sarcastic turn of events! For so long RL researchers cared about algorithms way more than environments, and no one paid any attention to priors — all RL experiments essentially start from scratch. But it took us decades of detours to realize maybe our prioritization should have be completely reversed.

But just like Steve Jobs said: You can’t connect the dots looking forward; you can only connect them looking backward.

The second half

This recipe is completely changing the game. To recap the game of the first half:

- We develop novel training methods or models that hillclimb benchmarks.

- We create harder benchmarks and continue the loop.

This game is being ruined because:

- The recipe has essentially standardized and industried benchmark hillclimbing without requiring much more new ideas. As the recipe scales and generalizes well, your novel method for a particular task might improve it by 5%, while the next o-series model improve it by 30% without explicitly targeting it.

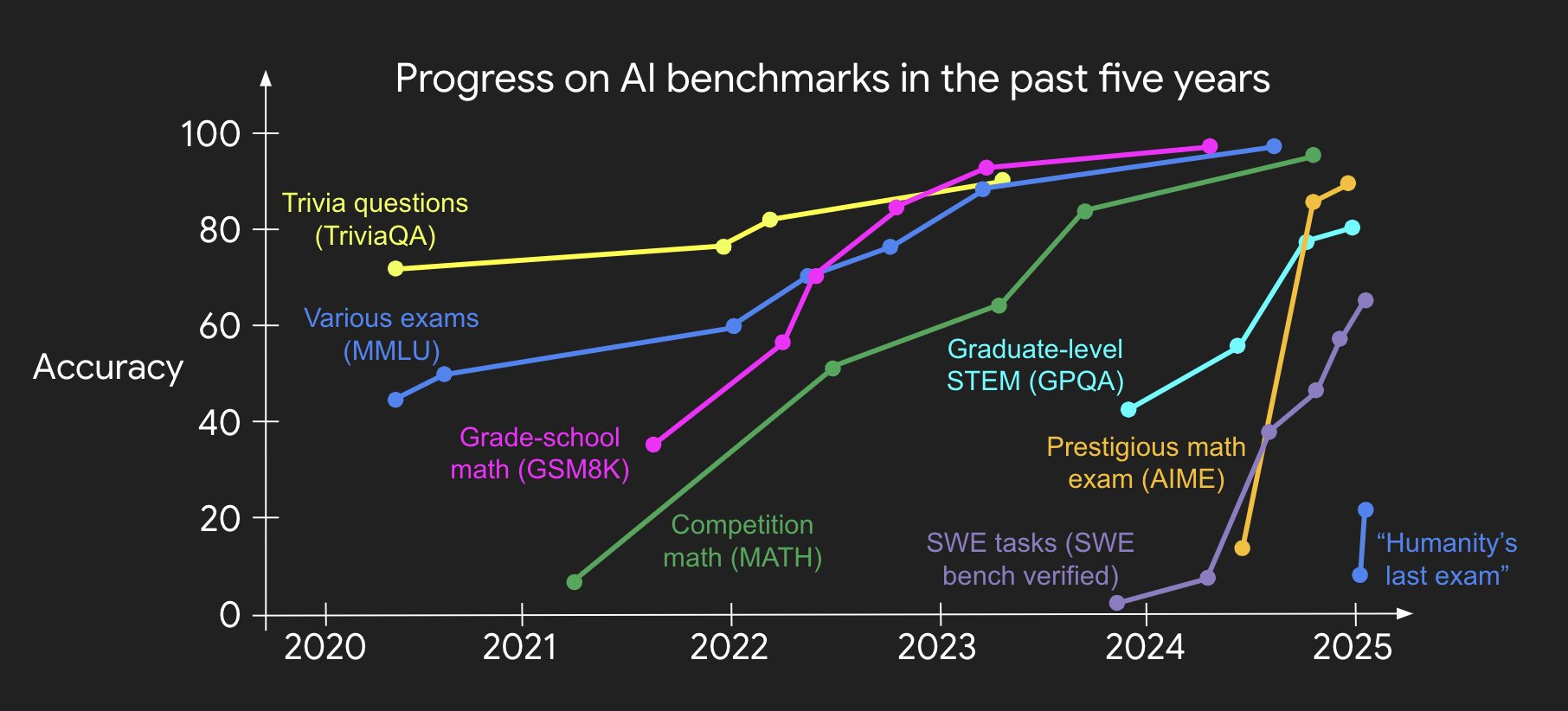

- Even if we create harder benchmarks, pretty soon (and increasingly soon) they get solved by the recipe. My colleague Jason Wei made a beautiful figure to visualize the trend well:

Then what’s left to play in the second half? If novel methods are no longer needed and harder benchmarks will just get solved increasingly soon, what should we do?

I think we should fundamentally re-think evaluation. It means not just to create new and harder benchmarks, but to fundamentally question existing evaluation setups and create new ones, so that we are forced to invent new methods beyond the working recipe. It is hard because humans have inertia and seldom question basic assumptions - you just take them for granted without realizing they are assumptions, not laws.

To explain inertia, suppose you invented one of the most successful evals in history based on human exams. It was an extremely bold idea in 2021, but 3 years later it’s saturated. What would you do? Most likely create a much harder exam. Or suppose you solved simply coding tasks. What would you do? Most likely find harder coding tasks to solve until you have reached IOI gold level.

Inertia is natural, but here is the problem. AI has beat world champions at chess and Go, surpassed most humans on SAT and bar exams, and reached gold medal level on IOI and IMO. But the world hasn’t changed much, at least judged by economics and GDP.

I call this the utility problem, and deem it the most important problem for AI.

Perhaps we will solve the utility problem pretty soon, perhaps not. Either way, the root cause of this problem might be deceptively simple: our evaluation setups are different from real-world setups in many basic ways. To name two examples:

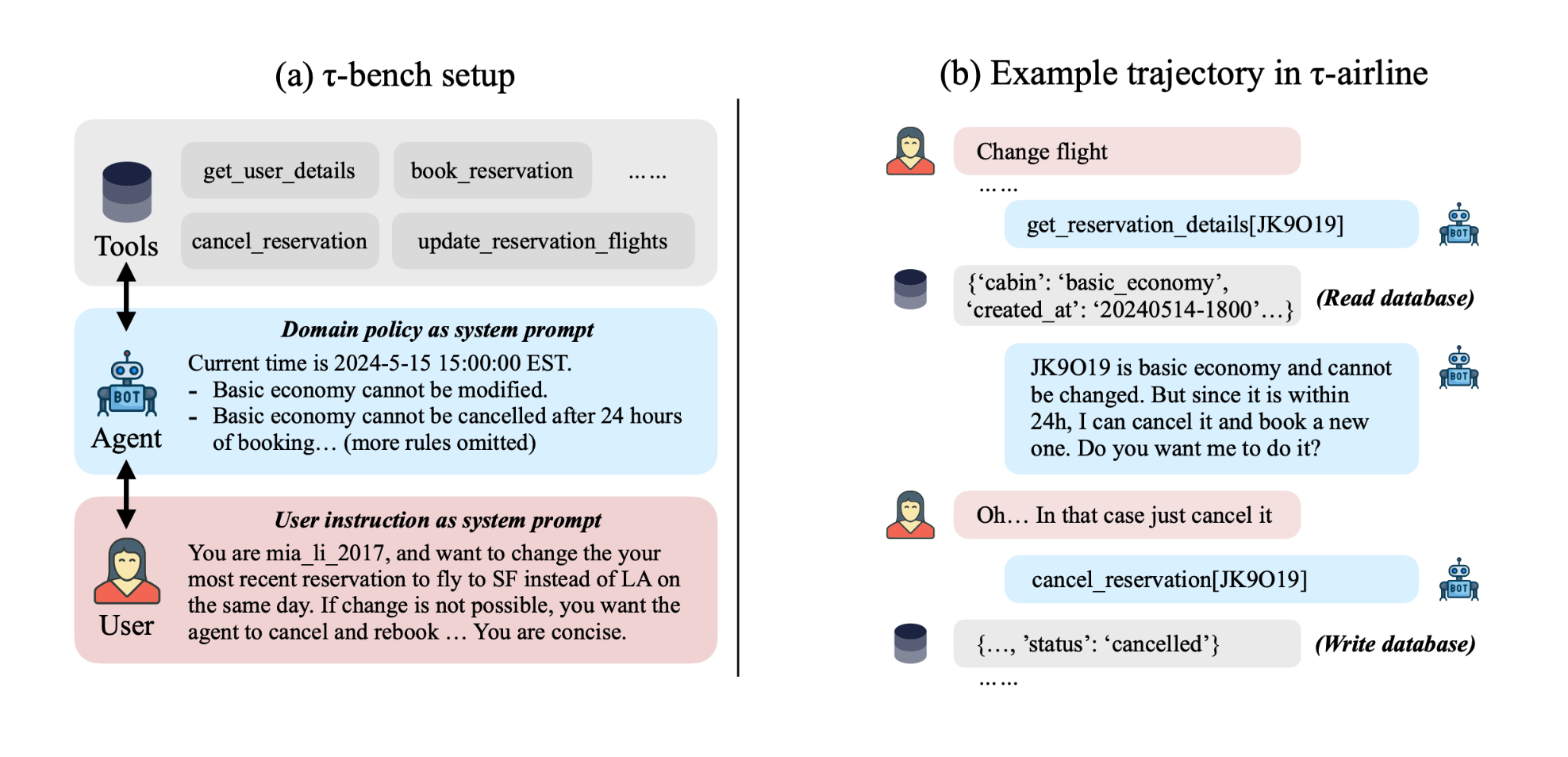

- Evaluation “should” run automatically, so typically an agent receives a task input, do things autonomously, then receive a task reward. But in reality, an agent has to engage with a human throughout the task — you don’t just text customer service a super long message, wait for 10 minutes, then expect a detailed response to settle everything. By questioning this setup, new benchmarks are invented to either engage real humans (e.g. Chatbot Arena) or user simulation (e.g. tau-bench) in the loop.

- Evaluation “should” run i.i.d. If you have a test set with 500 tasks, you run each task independently, average the task metrics, and get an overall metric. But in reality, you solve tasks sequentially rather than in parallel. A Google SWE solves google3 issues increasingly better as she gets more familiar with the repo, but a SWE agent solves many issues in the same repo without gaining such familiarity. We obviously need long-term memory methods (and there are), but academia does not have the proper benchmarks to justify the need, or even the proper courage to question i.i.d. assumption that has been the foundation of machine learning.

These assumptions have “always” been like this, and developing benchmarks in these assumptions were fine in the first half of AI, because when the intelligence is low, improving intelligence generally improves utility. But now, the general recipe is guaranteed to work under these assumptions. So the way to play the new game of the second half is

- We develop novel evaluation setups or tasks for real-world utility.

- We solve them with the recipe or augment the recipe with novel components. Continue the loop.

This game is hard because it is unfamiliar. But it is exciting. While players in the first half solve video games and exams, players in the second half get to build billion or trillion dollar companies by building useful products out of intelligence. While the first half is filled with incremental methods and models, the second half filters them to some degree. The general recipe would just crush your incremental methods, unless you create new assumptions that break the recipe. Then you get to do truly game-changing research.

Welcome to the second half!

Acknowledgements

This blog post is based on my talk given at Stanford 224N and Columbia. I used OpenAI deep research to read my slides and write a draft.